The time I was short on money in Africa [ A guide-interpreter / translator: Mika Shiraishi ]

I currently work as a guide for tourists coming to Japan from abroad. My job involves showing them around the country, introducing the unique culture found here, and granting their wishes to experience certain ways in which Japanese people live.

This is a story of something that happened roughly ten years ago, back when I still had no clue that I would be working as a guide in the future. I was staying in a certain refugee camp in Ghana. Having set out on a journey a year earlier in hopes of connecting the little minds of the world through the Internet, I was able to arrange a stay of just one month in this camp thanks to some my friends made on my travels so I could help improve the IT skills of its community.

One day, I left the camp and went to the post office in the next town over. I was trying to make a change via “tro tro” and send presents to friends in Japan.

The “tro tro”. This vehicle that makes a cute sound is a Ghanaian passenger bus. Old vans that had been driven almost to the point of being junked in Japan are sent to Africa, where they continue their services even longer, driving about town carrying passengers with the “XX Building Firm” still printed on their sides in Japanese.

The fare within the city is a few dozen yen for 30 minutes. It costs 100 yen (about one dollar) to go outside the city. The toro toro I rode made a leisurely progression to the next town, picking up various passengers along the way.

Post offices in Ghana are, frankly put, a real pain. No transaction ever ends with “I want to send a package” “Certainly” like they do in Japan. You report the details of what you’re sending at this window, fill out the paperwork at that window, get the package checked over at this other window, and then finally head over there to pay. They conduct strict screenings at each window to make sure there aren’t any falsehoods in your report. The presents I had went to such pains to wrap prettily were all opened and looked over. My packages were perhaps a little too nice looking, so the post office staff suspected of trying to disguise something else as soap, of all things. So, on this particular day I had to explain things even more thoroughly than usual.

After much time, I managed to convince them, and was finally able to move on to the payment part. At last, I can send my presents to Japan! Several hours had already passed since I departed from the refugee camp.

The thing is, once it became time to lay down the money...I was 100 yen short! That’s right, the soap I had bought at the fancy shop geared towards foreigners was more expensive than expected, and that was why didn’t have enough money. I had the toro-toro fare to think about, too, so I couldn’t just spend all the cash I had on hand.

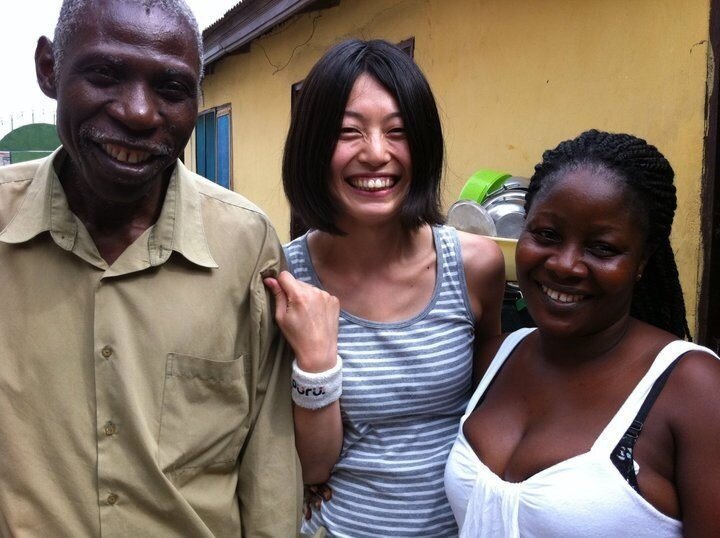

“I don’t have enough money, so I’ll come back tomorrow. I’ll go through the whole process again when I do,” I stated, and was about to leave when someone quietly held out a bill for the equivalent of 250-yen (about 2.27 dollars) from behind me. I turned back to see a lovely couple with big smiles on their faces.

“Don’t worry, we’ll take care of it for you.”

“Aid” is a word you hear a lot when visiting Africa. There are offering aid, and those receiving it. If you divide everything up so simple and straightforward like that, it’s easy to simply assign everything in the world into neat little folders.

But, was this African couple really part of the side that receives aid? Were the people I had met during my travels part of that group too? I had to wonder if people like this couple who felt the urge to help someone before them like it was the natural thing to do were really in a position where all they were doing was receiving aid.

During my travels here, in this nation in West Africa that sees barely any tourists from overseas, I met so many people who offered me a friendly helping hand.

There were many times when I rode the toro-toro that someone sitting next to me ended up paying my fare as well. I also had people who, when I asked for directions, accompanied me to the taxi stand, negotiated prices for me, and even paid the cost of the ride. When I told the taxi driver that I had quit my job before starting my travels, he introduced me to some work that it seemed like I could do. He even coached me on what to say in the interview.

Offer help if you see a person in need, and ask for it if you’re the one who needs assistance. It took coming all the way to distant Africa for me to realize this very natural thing, that maybe this is an essential nature of interactions between people.

It’s been ten years now since that trip. I’ve become a guide based out of Hida in Gifu Prefecture who shows travelers from overseas around Japan. This is something that happened just two weeks ago. I had just finished a guide job in Kyoto and was in the lounge of the inn when a traveler came up to me and said, “Excuse me. Can you exchange this 500-yen coin for 100-yen coins?” He wanted to use the coin laundry machine, but apparently the moneychanger was out of order.

“It’s okay, I’ll pay for it.”

Now it was my turn to say those same words that the couple in Ghana had said to me that day.

Mika Shiraishi

A guide-interpreter/translator for all of Japan. Based out of Hida, Gifu Prefecture. After traveling the world, she now shows visitors from abroad the true lifestyle and culture of Japan.